Both Things Can Be True: Bias and Bad Fundraising Advice

There are 99 problems, but they fall into different categories than you might assume.

Fundraising takes a long time.

I’m a female founder.

I don’t have a technical co-founder.

I don’t have enough traction.

These are all of the things I heard from a founder that I recently backed. She was pitching for a pre-seed round of $400k. I committed to the round, but I wanted to see her raise a bit more—at least $750k, but perhaps up to $1.5mm. I appreciated her desire to get back to work, but I convinced her to agree to a 2-3 week sprint. I reached out to about 15-20 other investors, of which about half were interested in taking a meeting.

She wound up with over $2.5mm of interest—and that’s not even counting the investors who indicated interest that we, unfortunately, had to ghost/slow walk (sorry!) because the round quickly filled up.

So what about all of the above statements—things that founders widely hold to be true barriers to fundraising? Was she just an anomaly or is there something else going on here?

The startup ecosystem is a terrific manufacturer of bad fundraising advice. Founders hit the street with their pitch deck, some make it, and some don’t, but nearly all of them ascribe a lot more human influence over the process than there probably is.

They imagine it to look something like this:

They think that there are some deals that are automatic yeses and some that are just bad, but there’s a whole lot that are kind of in the middle—deals that can be nudged over to one side or the other based on things like clever fundraising strategy or the presence of bias.

This isn’t surprising. Every founder believes what they have is fundable, otherwise they wouldn’t try. Therefore, when an investor passes, they’re very likely to believe that there’s some other factor at play other than just being a poorly thought out, unworkable, too small or otherwise problematic idea.

It’s not me, it’s them.

On the positive side, funding happens so rarely, that you’re inevitably going to be asked how you did it—and it’s just human nature to think that it’s something you did, versus the inherent awesomeness of the idea, the team’s relevance to the challenge, etc. They’ll tell you all about their strategy, the order of operations of who and how they pitched, the magic slides, the timing of the raise itself, etc. It will all very much make sense. They did X, Y and Z which seems really smart and the outcome was a bunch of money raised right away. You didn’t do any of those things and your raise took forever, so it must be causal, right?

Wrong.

You just don’t hear about all of the people who walked into a fundraise, “screwed it up” eight ways to Sunday and still walked out with the cash.

The reality is that fundraising looks more like this:

Show me a big opportunity, a great plan, a team whose career has led up to this moment through their experience and homework and show something outstanding that they pulled off that separates them from the pack—a “rabbit out of a hat”, if you will—and I’ll show you a funded team. What counts as a rabbit? Anything from intense customer love despite barely even having a product, pre-sales, a deal for access to data that creates a moat that no one else has—the list goes on. It’s the “hook” that gets a team noticed in a partner meeting.

Any VC will tell you that the ones they said yes to, they mostly got there right away—and that there are very few “maybe” deals that get tipped over the fence.

But wait—does that mean I’m saying there’s no bias in the process? Or that venture capital is a meritocracy?

Hell no.

It just doesn’t play the kind of role you may think it does.

So how come the numbers are so skewed in favor of white men?

Nearly half of the teams I’ve backed have female founders. I’ve backed multiple Black founders and entrepreneurs from the LGBTQ community and so I’ve seen a very wide mix of founders pitch, get funded and get passed on. I’ve seen lots of bias in how founders get treated and lots of differences in the way different types of founders pitch.

To me, the math doesn’t tell the whole story.

In fact, just quoting the math is a really lazy way of diagnosing the problems in the ecosystem.

Here’s the way I look at the math:

Let’s go over the structural bias first—the “pipeline” that happens before you ever even get near a VC.

The population is made up of about 30% or so white men—so, not knowing anything about who is pitching, all things being equal, that’s the starting point we’d expect to observe in terms of who gets funded.

This doesn’t take into consideration, however, that venture capital is a financial product—a product that works for some people and doesn’t work for others.

What are the characteristics of this product?

Well, if you add it to your startup, it does a few things. One, it usually implies that you’re going to start going cash flow negative to accelerate growth. That adds risk. Any company that takes on venture capital dollars is going to increase the risk that they’re going to have nothing to show for all their effort.

So, who is likely to be ok with that?

Well, for starters, you’d imagine that someone who is going to be ok with showing a zero is someone who probably feels like they have something to fall back on as well as someone whose personal and even family financial situation is strong enough to take the hit during prime earning years.

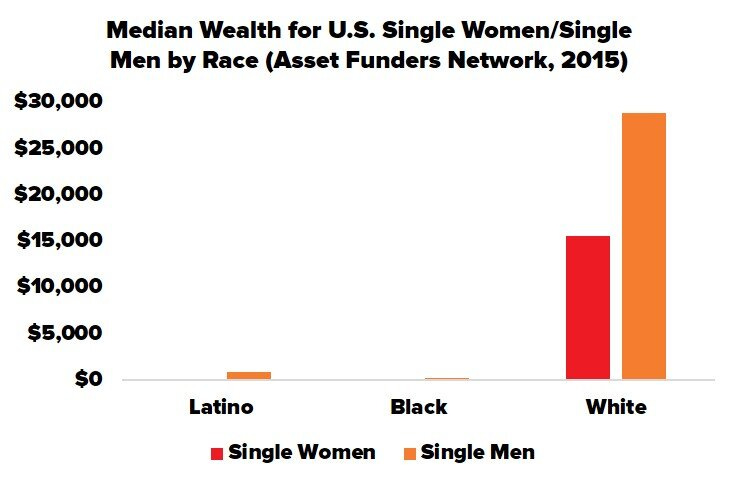

We know what the racial and gender wealth disparity looks like:

This is a lesson taught to be by Jewel from Collab Capital. It’s a way of looking at venture that I never thought of before—that venture capital and its distribution of ending outcomes is probably not something you’re going to go after if you don’t have at least a little bit of wealth cushion and definitely not if you’re already under water. I’m going to call this the risk/wealth effect and it definitely nudges the numbers towards the funding of wealthier white men.

Here’s a similar chart when it comes to student debt:

What you’re seeing here is the result of lots of systematic racial and gender inequity that happens even before the venture capital process starts. These are real problems that need to be addressed.

What we do not know is how many people are deciding to seek out venture capital from each group. It’s probably the most important statistic in the whole process—and no one captures it at any scale. For all we know, white men make 99% of the pitches. Now, we know that isn’t true—but without knowing what the number actually is, it’s difficult to accurately diagnose problems and track the efficacy of solutions.

If I was to guess, the demographics of people pitching me are reflective of two things—what my own network looks like and what my portfolio looks like. Given that I have a more diverse portfolio than most I would say that on average my gender pitch split is perhaps about 50/50. As for the percent of my deal flow that is BIPOC, I would say maybe about 20% or so, but I’m honestly not sure, since I don’t intentionally look up any photos as part of the initial pitch process and not everyone includes them. As for LBGTQ, I probably trend higher than average as I know several founders who have indicated that they’ve gotten my name off of various lists of allies and such. I do seem to be the absolute worst at figuring this out on my own as I can think of at least three founders that I’ve backed that turned out to fall into this category that I would not have assumed. This seems to be a trend in the rest of my life, too, not that one should ever make assumptions.

What all the media and conversational focus seems to be on is the middle part—the implicit or explicit bias you encounter in the process itself.

I’m going to break this up into three parts.

First is network bias. This is the requirement that you have to already be in the circle of a VC—a group of people that is largely straight white dudes—to be able to pitch, because of the requirement of a warm intro.

This is lazy, sexist, and racist—and also stupid because it has no provable impact on deal flow quality. Does doing the extra work of getting coffee with someone I know make you a better founder? No.

Also, I would argue that straight white guys will ask anyone they know for an intro, no matter the strength of the connection. They don’t see it as a burning of social capital, and so even if their networks aren’t better, they see no downside to asking, making it another way the process is skewed in the direction of favoring white men.

It needs to end.

The next part of bias I think is the most underestimated one—it’s how people from different groups pitch and make asks.

I’ve seen it time and time again. White guys tell you what could happen and everyone else tells you what is most likely to happen. Since pitching is about sharing your vision of the future, that’s going to make the pitches of white guys seem bigger, bolder, and more aggressive, which is exactly the kind of trajectory VC’s need economically to return their funds.

Does that mean the exit outcomes are any different? No, but it does change how the pitch is interpreted.

Why does this happen?

For one, our society scrutinizes white men less. If you’ve turned on the news in the last 100 years, you’ll see that, on the whole, the penalties and consequences for white men doing anything wrong are less severe. Therefore, getting it wrong on a pitch and not coming through on your predictions is a thing that we’re going to be much more comfortable with. The whole process feels less like a promise to us and we’re just a lot more comfortable shooting our mouths off about how big this thing is going to get.

Whenever I suspect that someone who isn’t a white male is sandbagging their pitch with the probable vs the possible, I’ll turn around and ask the question—is it possible this is an IPO? Is it possible this gets to $100mm in annual revenue?

The answer is usually a very confident “Yes!” and I think more VCs need to ask this question, and not fault entrepreneurs for starting out of the gate with that. Operationally, I’d rather founders focus on what’s probable so I shouldn’t ding them too much for not making up a whole other set of predictions for the pitch.

This is one of the biggest reason I think diverse founders lose out on funding—the unwillingness to talk big about the future and the laziness of VCs to ideate on the possible. We’ve seen studies on how men and women get asked different questions, but I also think it’s incumbent upon all founders to control the conversation. Don’t just let VCs ask all their questions and sit passively while they dictate your narrative. Make sure they’re asking all the right questions and tell them when they’re not.

Does this mean we should be telling everyone to pitch like white men?

No, but we should be telling everyone that an equity investment is an investment in the future—and we should remind them that probably this company isn’t going to work out, so reminding people what could happen if it does work out is a good fundraising strategy.

If you want to call that a “white male approach” have at it, but I actually thing it’s more about relating to the needs of the buyer of your equity.

Lastly, you’ve got the racism, sexism, and willful ignorance that happens in a meeting as part of the evaluation process. That is 100% a part of the daily life of anyone who isn’t a white guy and it would be wrong to deny that it is there. I just think that it’s, on the whole, not the biggest reason why someone passes on you.

It also leads me to something that I’ve said often: “Both things can be true.”

It can be the case that someone said something to you or treated you in a way that was dismissive because of who you are AND that you really haven’t met any kind of objective bar for being successful at fundraising. If you pitch someone who is sexist with very little growth or an unworkable idea, you’re most likely going to feel mistreated in the meeting, but also the same company run by a guy wouldn’t have gotten funding either.

That’s an easy thing to forget. While most of the funding goes to white men, most white men are also getting turned down for money.

The last part of why the numbers are so off is again, the laziness of how people are evaluating the data—the pure math of it.

When Stitchfix went public, Katarina Lake raised less than $100 million—meaning she owned more of her company than most founders do by the time she got to that milestone. Rationally, anyone would argue that’s a good thing, but in terms of the ecosystem analysis, she’s not helping.

By not raising, and being successful on less money, she’s making “the stats” worse. That’s the same for Marcela Sapone, founder of Hello Alfred, who in eight years of being in business, has only raised a Seed, an A, a B, and a C.

Compare that to another proptech company, VTS, that roughly started around the same time, who has raised one more round, which gives it two times the funding.

Who is running their company better?

Is the market being unfair?

Who knows—but I do know that it was Marcela’s intention to build up profitably before she stepped on the gas, and so she went three years between her Series A and her Series B without even attempting to go to market.

I suspect there are a lot of later stage companies run by female founders not wanting to just keep raising round after round for as much money as possible. goTenna is a BBV portfolio company where I know this to be the case. It’s a hardware company that I know Daniela Perdomo runs as efficiently as possible because she doesn’t want a huge overhang of capital sitting on top of her. She sees that as the best way to run her business.

Given how much larger later stage rounds are, if anyone who isn’t a white male is focusing more on profitability and less on just raising over and over again, that’s really going to throw off the annual numbers—because you have that percentage of women who are in market, but just skipping rounds or years.

The other thing you’ll see are these megarounds—the long tail of companies like Uber, Airbnb and WeWork that raised multi-hundred million dollar or billion dollar rounds before going public or trying to get acquired. Is that a good strategy? Is that something we think more women and BIPOC founders should be doing?

If they want to do that, we need to make sure that market is available to them—but sometimes these rounds feel a little bit like buying a Ferrari. A Ferrari is a completely impractical and overpriced car for what it does.

Could you imagine trying to measure the equity of transportation by measuring the price of the car purchased?

It’s important that the funding markets work for founders based on what they want for their companies—and it’s very clear to me that in many ways, sometimes because of bias and issues of access, they do not.

It’s also clear for me that the way we talk about this inequity is inadequate, and a bit lazy about telling the whole story about where the problems are—and sometimes VC just isn’t a desirable product for founders.

Both things can be true.

We need to make networks more accessible and change who is on the other side of the table so we don’t have monolithic assumptions about what makes a good pitch.

But we should also stop glorifying raising for the sake of raising. Raising capital is a gateway to growth, but it isn’t the only one, and it’s also ruining some perfectly good businesses that get into trouble because they are overcapitalized and unfocused.

We shouldn’t be taking the advice of the people that are on this kind of track and weaving it into our own fundraising strategy.

Half the time, they don’t even really know why and how they got funding, nor do the VCs that backed them in earlier rounds.

That doesn’t stop them from hosting a Clubhouse room on it.

Very well written article. Gives me some hope as an African American founder even if it's a sliver